Vibe Check: Marital Surnames

Generational divides emerging over marital surnames

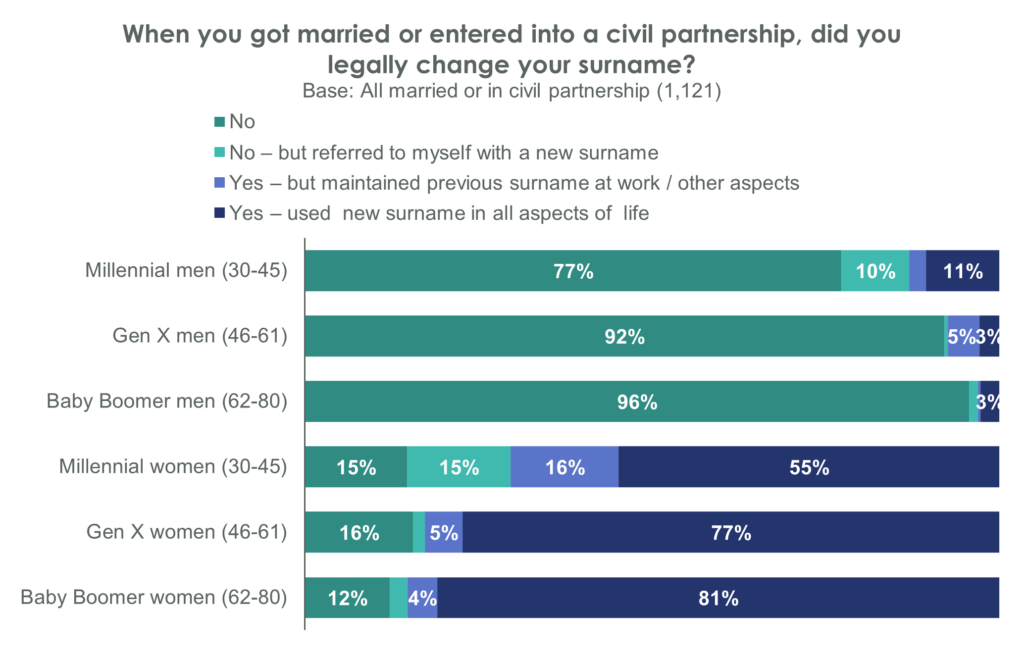

Among Brits who are or have been married or in a civil partnership, half (48%) legally changed their surname with the majority using it in all aspects of their life (42%), while 6% maintained their previous name at work or in another aspect of their life. A further 4% referred to themselves with a new surname but did not legally change it.

This, naturally, varies by gender. Four fifths (81%) of women have legally changed their name, as opposed to just 10% of men. Twice as many women (6%) as men (3%) also did not legally change their name but used their partner’s name or a new surname to refer to themselves; in fact, just 13% of women did not change or use their partner’s surname after getting married.

Beyond this perhaps unsurprising gender split, Brits’ behaviours vary by generation. Indeed, married Millennial women were least likely of all generations to change their surname and use this in all aspect of their life (55%), as opposed to Baby Boomer women (81%). They were equally likely not to have changed their name (15%), not have changed their name but referred to themselves with a new name (15%), or have changed their name, but maintained their previous name at work or in other aspects of their life (16%). Similarly, Millennial men (10%) were ten times as likely to refer to themselves with a new name despite not legally changing it than Gen X or Baby Boomer men (1% for both).

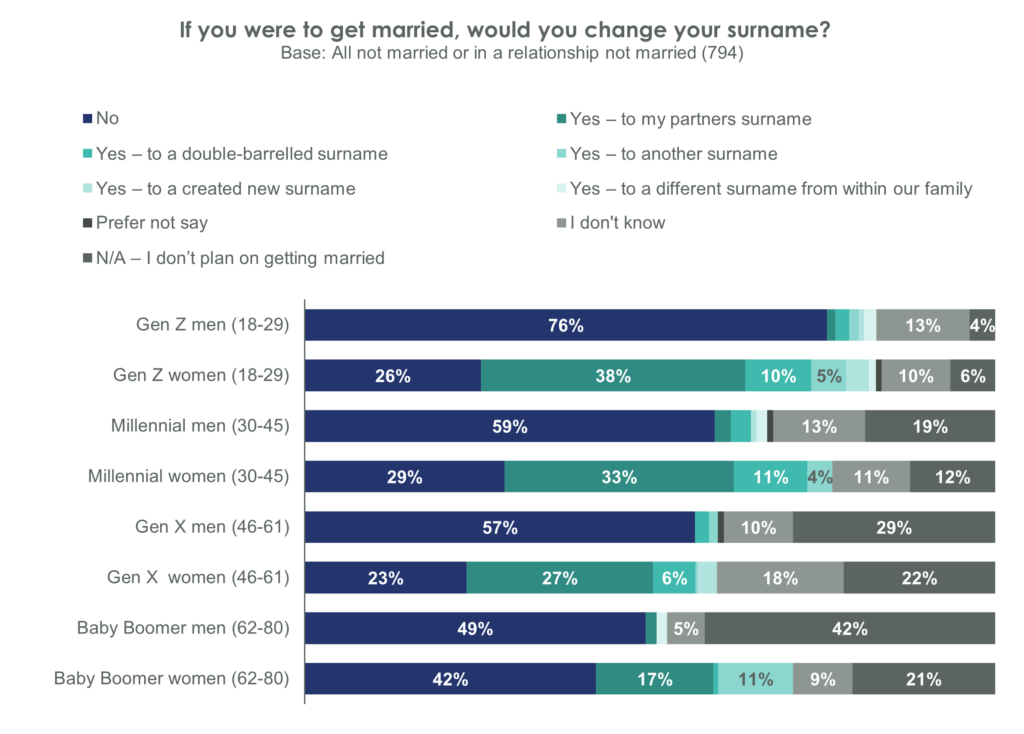

This theme continues among those have not been married or are in a relationship not married. Indeed, the majority of Gen Z men would not change their name (76%) – although this is notably lower than the proportion of all men who have married and did not change their name (87%). On the flip side, just under two-fifths (38%) of Gen Z women would change their surname to their partner’s, as opposed to 75% of women who have changed their last name and chose their partner’s name. In general, Gen Z women were more likely to prefer alternative approaches, such as double-barrelled surnames (10% vs 2% of men in that generation), other surnames (5% vs 1%), or creating a new surname altogether (3% vs 1% Gen Z men). Likewise, Millennial women were also significantly more open to double-barrelled surnames (11%) than men from their generation (3%). Interestingly, Baby Boomer women would be more likely than their younger counterparts to want to keep their surname (42%) or change their name to another one (11%).

A fifth preferred their previous surname

Of the 27% of Brits who have changed their surname because of marriage or civil partnership, most (86%) have changed it to their partner’s surname. Fewer than one in twenty opted for a different surname from their family (5%), opted for a double-barrelled surname (4%), while just 3% created a new surname for their new family unit.

Among women who changed their surname, their partner’s surname was the most common choice (92%). On the other hand, among men who changed their surname, taking a different surname from within their family (28%) was more popular than taking their partner’s surname (25%). This was also a common practice among married Millennials of both genders (11%).

Considering which surname they preferred, those who changed their surname tend to prefer the new one (42%), while a third (32%) have no preference, and just under a quarter (23%) preferred their original name. Interestingly, over two-fifths (44%) of women prefer their surname after getting married, compared to just a fifth (19%) of men.

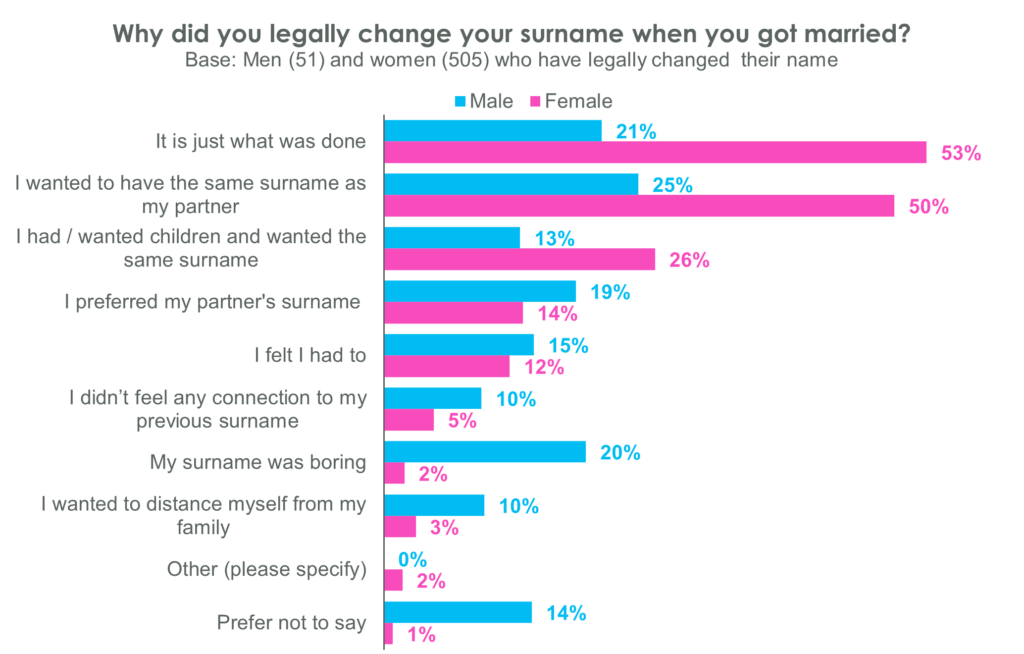

When looking at motivations of changing their name, over half of women did so because it was just what was done (53%), even higher for Baby Boomer women (60%), but less of a driver for Millennial women (36%). Half of the women also wanted to have the same surname as their partner (50%), while a quarter wanted the children to have the same surname (26%).

Interestingly, men were less likely to change their surname for those practical reasons, with just a quarter (25%) wanting to have the same surname as their partner, and an eighth (13%) wanting their children to have the same surname. Indeed, a fifth changed it because their surname was boring (20%) or preferred their partner’s surname (19%), while 15% felt that they had to – higher than 12% of women. One in ten men (10%) also changed their name as they wanted to distance themselves from their family, as compared to just 3% of women, or felt no connection to their previous name (10% for men and 5% for women).

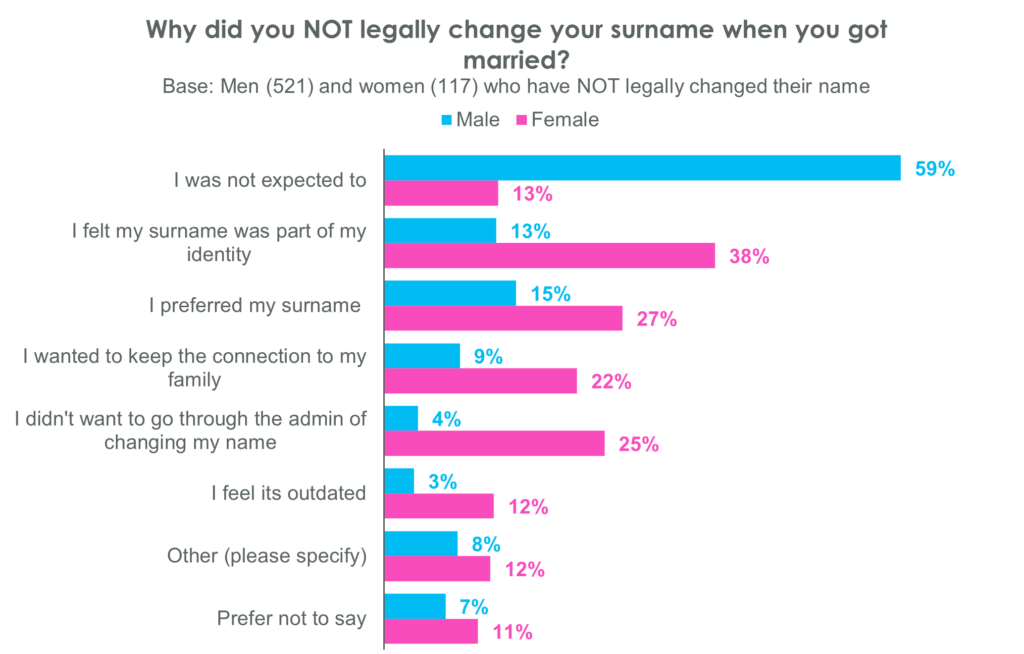

As for those who did not change their surname when getting married, most men (59%) felt that they were not expected to – significantly higher for Gen X (63%) and Baby Boomer men (61%). Among women, however, the leading motivation was feeling that their surname is a part of their identity (38%) and a preference for their surname (27%). A quarter also did not want to go through the admin of changing their name (25%), while over a fifth (22%) wanted to maintain the connection to their family. One in eight women also believed that this practice was outdated (12%).

A surname is for life, not just for marriage – 63% don’t change their name back after divorce

Among divorcees who changed their name, keeping the married name was the most common option (63%), while just a third went back to their original surname (34%) and fewer than one in twenty opted for a new surname (3%).

Among all Brits, the opinions are split on whether women changing their surname after marriage is outdated (27%) or not (34%), and interestingly, this split remains the same for both men and women. In terms of the generations, Gen Z (39%) and Millennials (35%) are more likely to agree with this sentiment, and men from those generations are more likely to believe that to be true than women (Millennial men 37%, Millennial women 32%).

On the flip side, over a third (35%) of Brits believe that men taking their partner’s surname after marriage is taking feminism too far, while a quarter (26%) disagree. In this case, two-fifths of men (44%) agreed with the statement, as compared to just 27% of women. Gen Z women were most likely to disagree with this sentiment (47%).

Just a fifth (18%) of Brits believe that people who change their surname after marriage lose their identity – although this is significantly higher for Gen Z (29%), and particularly men of that generation (32%). Those who did change their surname when marrying were most likely to disagree with this sentiment (70%). As such, among those who have changed their surname when getting married, the majority (77%) agree that having the same surname as their partner makes them feel like a part of a family unit.

Practical concerns could also prevent people from keeping, or changing, their surname, as over two-fifths of Brits believe that admin is much more difficult for married couples with different surnames (44%), with this notably higher for those who legally changed their name but kept their previous surname in some aspects of their life.

Looking back, just one in seven (14%) of those who have changed their surname regret it. Interestingly, this is significantly higher for the small proportion of men who have changed their surname (40%) than for women who have done the same (12%). Millennials of either gender were also more likely to regret this decision (21%). Those who have changed their surname to a double-barrelled, new, or different surname were also much more likely to regret this (44%) than those who changed it to their partner’s surname (10%).

It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that a fifth (22%) of those who have changed their surname would not do it if they were to get married now – once again significantly higher for men (55%) than women (19%) who have made that change. Interestingly, those who have legally changed their name, but maintained their previous name in work or another aspect of their life, were more likely to agree with this (51%) than those who used their new name in all aspects of their life (18%).

For those who have children, the majority gave them either their birth surname or the other parent’s birth surname (both 41%), with men most likely to give their child their surname (80%) and women their partners surname (72%). New trends though are coming through. Gen Z and Millennials are significantly more likely to have given their child a double-barrelled name (13% and 10%) or a different surname from within their family (8% and 5%), and Gen Z are five times more likely then parents of all ages to have created a new surname (10% v 5%).