Handicapping a second EU referendum campaign

Theresa May has survived a confidence vote of Tory MPs but has delayed almost certain defeat in the ?meaningful vote? in the House of Commons on the EU Withdrawal Agreement. Despite calls for May to go back to the negotiating table, the options MPs (and Britain) face have been clear for some time: May?s deal, no deal or Remain. When the vote in the Commons eventually happens, assuming the deal is rejected, what happens next is the question nobody quite knows the answer to. The idea of having a second referendum between the deal and Remaining in the EU has therefore gone from a fringe proposal dismissed even by leading Remain politicians to perhaps the only way to break the deadlock.

Breaking the deadlock is the key here. In polling, support for another referendum has increased but still isn?t a majority. This has generally been due to a hardening of support by Remain voters rather than Leave voters coming around to the idea. If a second referendum happens it will be more due to parliament being unable to find another solution than overwhelming public demand.

So, on the assumption that the various formidable hurdles to holding one have been cleared (passing the legislation, agreeing the question, the campaign rules, designating official campaigns for each side), how might such a campaign unfold?

On the face of it, the Remain vote is more united than the Leave vote by virtue of the fact that there is only really one Remain option vs. two Leave ones.

In a straight ?Leave with the deal vs. Remain? referendum, Remain beats May?s Deal by 45% to 33%. This isn?t run with our usual VI method but it?s a good indicator. However, while this is a healthy lead, it?s probably very soft. While 84% of 2016 Remain voters would choose Remain again, only 59% of 2016 Leavers would choose to Leave on the terms of the deal. 10% have moved to Remain but 19% have said ?don?t know?.

These numbers are no doubt affected by the high proportion of Leavers who don?t approve of the deal and think a better one is possible. In a referendum environment, once ?leave with the deal? becomes the default ?Leave? campaign, it?s very likely a large number of these people will come on board. Take the number of high profile Leave supporting politicians (Boris Johnson, Dominic Raab, Daniel Hannan) who have said that May?s deal is worse than Remaining. Would they, when faced with that deal vs. Remaining, stand by those statements?

A Remain campaign in a second referendum would have a number of strengths that the 2016 Remain campaign lacked.

The main one is structural. The Leave option this time would be a specific proposal with strengths and weaknesses rather than many different and conflicting ideas of what ?Leave? could mean. Although the argument of ?accept it for now and fix it later? may have some traction, it would be harder for Leavers to dismiss criticisms as easily as they did in 2016.

The second is both a strength and potentially a weakness. In 2016 Remain was the option supported by an unpopular incumbent government whose base and media supporters were largely against it. Labour – a party much more Remain-friendly and led by a man barely comfortable sharing a platform with former Labour prime ministers let alone a Tory ? and Labour voters had a dilemma between supporting EU membership and wanting to avoid helping a Conservative government. In a second referendum, Labour voters won?t just be asked to vote against Brexit but to vote against Tory Brexit, helping to resolve this dilemma. On our 10-point pro/anti Brexit scale, Labour Leavers are much less likely to be strong Leavers than their Conservative counterparts (47% vs. 72% of Conservative Leavers). 20% of 2016 Labour Leavers say they would vote Remain and just 52% to ?Leave with the deal?.

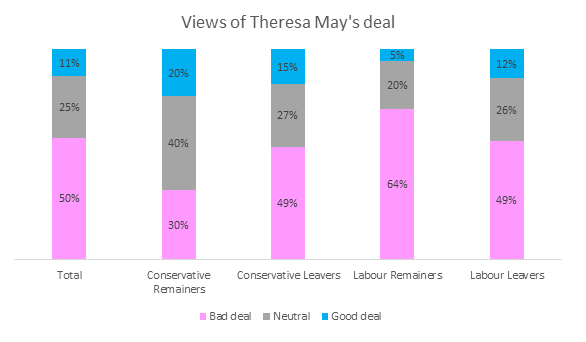

On the other side, Conservative Remainers are more likely to stick with their 2016 vote even though they are the only political group that seem to be coming out to bat for the deal. Views of the deal itself are poor. 50% believe it is a bad deal for the UK vs. just 11% saying it is a good deal and 25% neutral:

Just 13% of Conservative Remainers, however, would vote for the deal in a second referendum vs. 77% who would switch back to Remain. ?Leave with the deal? would therefore be relying an awful lot on voters focusing on the first word of that option rather than the others.

Remain has some key weaknesses of its own though, the most powerful of which is, as Theresa May put it in her conference speech, that we already had a ?peoples? vote and the people voted to leave?. Despite the vast majority of Remain voters still wanting to Remain, this argument cuts through.

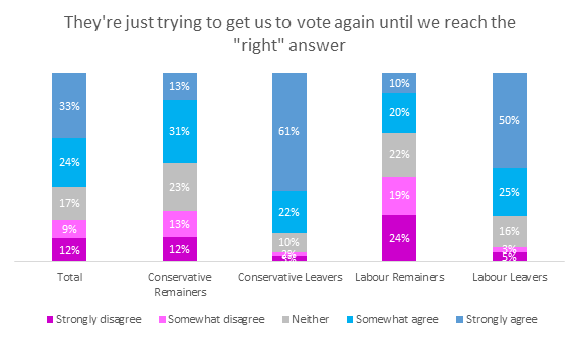

Over half (56%) of all adults agree that ?they?re just trying to get us to vote again until we reach the ?right? answer?. Among Leave voters agreement is, as one would expect, solid with 79% agreeing. But even Remain voters? views are, at best, split with 35% agreeing and 37% disagreeing. On our 10-point pro/anti Brexit scale, those placing themselves around the middle (so either neutral or very slightly leaning to or against Brexit) agreed by 48% to 8% with this statement.

Similarly, a substantial majority agreed with the statement that ?the question of whether to remain or leave the EU has been settled, the only question is ?how? we leave? with 60% agreeing and 21% disagreeing.

In contrast, agreement that ?we know a lot more now about what ?leave? means so it?s only right to hold another vote now that we know the specific terms? is much weaker, 41% vs. 37%.

So, the ?Leave with the deal? campaign could easily offset the weaknesses of having to advocate for an unpopular compromise by harnessing anger at the premise of a second referendum taking place at all.

Another key area of weakness for Remain mark 2 is who Leavers blame for the deal being a bad one. The most popular option is Theresa May (40%) and this is higher among Leave voters (46%) but Leavers are also far more likely than Remainers to blame the EU (33% selecting either Michel Barnier, the European Union or ?other European politicians / leaders? vs. 13% of Remainers). So far, so predictable. However, looking again at our 10-point scale, those we classify as ?soft Leavers? are the most likely to blame the European side of the negotiations (41% vs. 22% overall and 32% among hardcore Leavers). Given that any route to a Remain victory must go through convincing at least some Leave voters to either switch sides or stay at home, it?s a bad sign that the key target group for Remain are the most likely to blame the EU for a bad deal.

The final key disadvantage for Remain is that Leavers know their leaders. The mechanics of a second referendum will no doubt demand leaders on both sides. A campaign can be as grassroots led and disparate as it wants to be but, at some point, the broadcasters are going to need somebody to put in a TV debate and spokespeople to take part in interviews and these have a natural bias towards politicians and established public figures. In 2014 in Scotland we had Alex Salmond for ?Yes? and Alistair Darling for ?No?. The official leader of the 2016 Remain campaign was Conservative peer and former Marks and Spencer CEO Stuart Rose but it was still David Cameron and mostly other MPs taking part in the TV events.

When we ran an open text question asking people to name a public figure whose views on Brexit they respect, the most popular individuals named (aside from variations of ?nobody?) were all Leavers: Jacob Rees-Mogg, Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage. Few mentioned any prominent Remain-backing politicians and the only figure who could be described as Remain-aligned that was mentioned in any great quantity was Jeremy Corbyn.

Again, these are all figures who have come out strongly against Theresa May?s deal so they may find it awkward to campaign in favour of it. However, it merely highlights again how enormously important the framing of the referendum is and whether the debate focuses on the specifics of the deal or simply re-runs the 2016 referendum.

View the full tables VI Brexit Referendum.