Which Brexit strategy, if any, would get Labour an overall majority?

The Labour Party might look like it’s in trouble as we head into its annual conference in Brighton his weekend. But just in case we should all be planning for a majority Labour government when we come to our next general election, the question is what does that path to power look like?

Despite the Conservatives being in a minority government Labour is actually pretty far away from winning a majority due to the large number of third and fourth party MPs. The party won 262 MPs in the 2017 general election, meaning that it needs to gain 64 seats net to win a majority at a general election. But where are they? What do they look like? And how hard will it be for the Labour Party to win them.

Some simple numbers: the 64 seats to power

For full disclosure, we have excluded Scotland from the equation simply because the number of complicated outcomes north of the border in seats often with three potential winners is rather difficult to navigate. This means we’ve concentrated on the 64 numerically easiest seats to win in England and Wales.

Hence, the 64th target seat for Labour is Shrewsbury and Atcham. A seat the Conservatives have held relatively well since 2005, despite the seat going Labour in the Tony Blair landslides of 1997 and 2001. It would take a swing of only 5.7% swing to win, as one of the electoral features the 2017 general election left us with is a large number of Conservative-Labour marginals with relatively small majorities. And as 53% voted to Leave in the seat, it’s not drastically more Leave than the country as a whole. In short, this should be a sensible place for Corbyn to focus his efforts, but one does have to ask how he does?

What strategy does Jeremy Corbyn follow?

You could forgive Jeremy Corbyn’s wait and see strategy on Brexit when looking at the full range of seats he has to win back.

For a party that ultimately relies on Remain support, 43 out of the 64 target seats registered a higher Leave vote than the country as a whole. The worse part is that 17 of these seats are strongly Leave, in that they voted by 60% or more to leave the European Union: Mansfield (71% Leave), Stoke on Trent South (71% Leave), Telford (67% Leave) are all great examples from the Midlands that Labour are likely to struggle with although they all require only a 1% swing or less to win back.

But there are some soft Remain targets. But compared to those 17 uber Leave seats, there are only 5 target seats for Labour where Remain won 60% of the vote or more. The obvious examples of Putney (73% Remain), the Cities of London & Westminster (71% Remain) and Finchley & Golders Green (69%) should all be obtainable. But currently Labour’s remain vote is crumbling at the same speed as the Conservatives’ remain vote.

Even here the there a problems. A challenge from Chuka Umunna and a resurgent Lib Dems could upset the apple cart in Westminster. The continuing saga around anti-Semitism in the Labour Party might have helped keep Finchley, Hendon and Chipping Barnet out of Labour hands last time, and looks like it could do the same this time. These easy seats don’t look that easy in context.

London Remain seats or Midlands Leave seats?

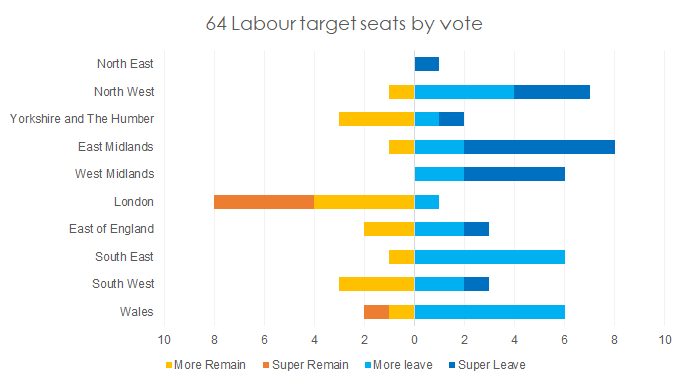

To demonstrate further how these problems interrelate, we have mapped these seats out across England and Wales by region and EU Referendum vote.

The first obvious thing to point out is that the regions with the two largest number of target seats for Jeremy Corbyn are the East Midlands and London, with 9 target seats a piece. But these two regions could not look more different.

How can Jeremy Corbyn genuinely build a campaign that unites young, diverse, prosperous London seats with aging, struggling and very white towns in the East Midlands? Remainers that were going to swap from the Conservatives to Labour did so in in 2017. This is why so many of their targets this time round are disproportionately pro-Leave, as Labour already won dozens of Remain leaning seats in 2017.

But the problem here is that if Jeremy Corbyn finds a way to get on board many of the Brexiteers he would love to win over in the Midlands and North, he risks being outflanked by the Liberal Democrats in the very places that gave Labour such a surprisingly strong showing last time. And surely cutting off his chances of winning back the urban centres of Remain dotted around the country, but focussed in London, as he disenchants Remain voters.

Currently it appears Labour’s best hope is preventing the Conservatives from winning a majority, rather than obtaining one themselves.